|

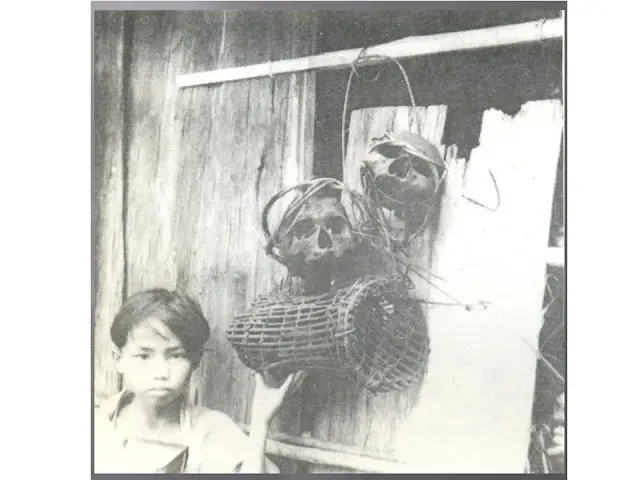

| The front wall of a traditional Dayak house before the 1970s: decorated with trophies from ngayau (headhunting). Today, they are symbols of past victories. Documentation: the author. |

Ngayau: An Exploration of the Cultural Significance and Transformation of a Dayak Tradition

Compiled by: Masri Sareb Putra, M.A.

Date: June 04, 2025

Abstract

The ngayau tradition in Dayak culture is often misunderstood and narrowly defined as headhunting. This paper explores the deeper essence of ngayau as a cultural mechanism for territorial defense, the preservation of honor, and the affirmation of identity among the Dayak people of Borneo. Far from being an act of unprovoked violence, ngayau carries spiritual, social, and historical significance. Drawing on Masri (2017), the study outlines ngayau’s fourfold evolution; from headhunting to modern symbolic interpretations of resilience and excellence. Through historical analysis, ritual description, and cultural insight, this article aims to correct misconceptions and emphasize ngayau’s enduring importance in Dayak identity.

1. Introduction

The Dayak peoples, indigenous to the island of Borneo, are renowned for their rich and diverse cultural traditions. Among these is ngayau, a practice commonly misrepresented by outsiders as mere headhunting or tribal violence. In truth, ngayau functioned as a vital institution of territorial defense, honor, and cultural integrity.

This article explores the meaning of ngayau, situating it within its historical context and mapping its transformation across four distinct phases, as identified by Masri (2017). By delving into its rituals and purposes, we aim to reveal the complexity of ngayau and its role in shaping and preserving Dayak cultural identity.

2. The Misunderstood Essence of Ngayau

2.1 Beyond Headhunting

Contrary to popular belief, ngayau was not merely the act of taking enemy heads as trophies. Its primary aim was the defense of territory and clan honor. Among many Dayak subgroups, such as the Iban of West Kalimantan and Sarawak, ngayau served as a structured cultural expression of protection and prestige.

2.2 Cultural Significance

Although practiced differently across Dayak subgroups, the essence of ngayau remained consistent: protecting the land, community, and cultural values. It was a ritualized act imbued with spiritual significance and communal discipline—an embodiment of resilience, unity, and survival.

Read Persebaran dan Identitas Budaya Suku Ketungau Tesaek di Kabupaten Sekadau

3. Historical Context and Ritual Practice

3.1 Origins and Structure

The ngayau tradition was especially prominent among the Iban Dayak, connected to both individual and collective warfare. It was institutionalized by leaders like Urang Libau Lendau Dibiau Takang Isang, who earned the honorary title Keling Gerasi Nading from Merdan Tuai Iban. Ngayau took two primary forms: Kayau Banyak (mass raids) and Ngayau Anak (individual ventures). Successful warriors earned the revered title Bujang Berani (brave knights).

3.2 Ritual Preparation

Preparation for ngayau involved assembling both spiritual offerings and war equipment. Items included:

-

Ritual materials: pulut plates, tempe, rendai, chicken eggs, betel leaves, gambir, cigarettes, lime paste, areca nuts, tobacco, ketupat, rice, jalong cubit, thread, and utai bekaki.

-

Weapons: sangkok, terabi, tersang, mandau, and symbolic flags in red, green, yellow, black, and white.

-

Roles were divided: women prepared offerings (pedara), while men readied weapons and provisions.

3.3 Ceremonial Process

The village leader performed mantras and blessings, passing a chicken three times over the warriors’ heads to invoke protection. Ancestral spirits were summoned. The act of scattering roasted paddy (tumpe) symbolized a pure conscience.

Before battle, a pig was sacrificed and strategies laid out. Enemy heads—when successfully taken—were placed at the entrance of the Betang (longhouse) and celebrated through storytelling. Offerings were also made to panggau (divine beings), with a three-day vigil to prevent bad omens.

3.4 Climax and Celebration

Weapons were ritually blessed. Blood from sacrificed chickens was smeared on warriors’ feet and foreheads, believed to ward off evil. Victorious warriors returned to dance, placing severed heads (or symbolic coconuts) before the Betang. Inside, blood was anointed on the heads, tuak (rice wine) flowed, and ceremonial dances expressed gratitude to the spiritual world.

Read Proses dan Konsep Adat Perkawinan Dayak Jangkang

4. The Fourfold Evolution of Ngayau

Masri (2017, pp. 436–440) outlines ngayau’s evolution through four phases, adapting to socio-cultural changes while retaining its core function—mastery, survival, and sovereignty:

-

Headhunting Era

The earliest phase, characterized by physical warfare and severing heads, served both defense and offense in protecting territory and community. -

Sports Domain

As violence waned, ngayau shifted into symbolic “trophy hunting,” rewarding excellence in competitive or athletic domains. -

Strategic Human Resources

In modern professional settings, ngayau was reinterpreted as a strategy to “hunt” skilled individuals—recruiting talent across sectors. -

Modern Intellectual Era

Today, ngayau is expressed through intellectual and cultural resilience—targeting ignorance, backwardness, and poverty. The tools have changed, but the spirit of Dayak survival and self-determination endures.

5. Post-War Celebration and Modern Legacy

Among the Dayak Jangkang (a Bidayuh subgroup), returning warriors were greeted with joyful ceremonies. Women offered food, tuak, and dances, while the young were inspired by acts of bravery.

The closing ritual, notokng, involved dancing around the enemy’s head (naja baa’)—now symbolized in cultural reenactments. In contemporary times, ngayau persists not in violence, but as an emblem of the Dayak spirit: heroic, unconquered, and adaptive.

6. Conclusion

Ngayau is far more than an act of headhunting; it is a cultural system built on defense, dignity, and identity. Its rituals reflect profound spiritual and communal values.

Through its fourfold transformation, ngayau has remained relevant to the Dayak people, symbolizing courage, excellence, and resilience. In the face of modernity, preserving the spirit of ngayau is crucial to sustaining the richness and legacy of Dayak civilization.

Posting Komentar